China Bans Imports of Foreign Waste to Combat Pollution

China Briefing 24 October 2017 | Alexander Chipman Koty

China will ban the import of 24 types of waste by the end of the year as part of a campaign against “foreign garbage”.

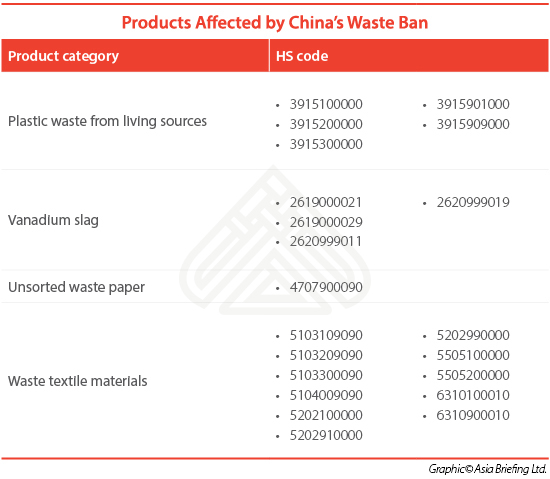

The ban was announced by five government agencies in July and will go into effect on December 31, 2017. It affects several classes of waste including waste plastic, glass, slag, waste wool, ash, cotton, yarn, and unsorted paper.

The ban has already affected both overseas exporters of waste and China-based purchasers of waste, as well as companies who purchase raw materials made from reprocessed waste.

Many developed countries depend on Chinese demand to handle their excess waste, which Chinese recyclers purchase, sort, process, and subsequently re-sell. As a result of the ban, prices of materials like paper and plastic have skyrocketed, driving up costs for businesses reliant on cheap recycled goods.

Waste imports in China

China’s industrial boom helped spur the growth of its immense recycling industry, as recyclers provided manufacturers with cheap materials to produce their goods. The appetite for raw materials from the manufacturing sector led China to become the world’s largest importer of foreign waste.

Last year, China imported over US$18 billion worth of waste, mostly coming from developed countries such as the US and Japan. It imported 7.3 million metric tons of waste plastics alone, representing 56 percent of the world total, valued at US$3.7 billion.

According to the Wall Street Journal, in 2016 over two-thirds of the US’ waste paper exports and over 40 percent of its discarded plastic exports were sent to China, while paper and plastic scrap exports to China were worth over US$2.2 billion. The EU27 is similarly dependent on China to take its waste, as it sends 87 percent of its recycled plastic directly or indirectly to China.

Chinese recyclers reprocess waste to make a wide range of usable materials for re-selling, such as cardboard and yarn. Businesses – both domestic and overseas – purchase these goods at an affordable rate, and are also able to market their use of recycled materials.

However, while businesses tend to tout their environmentalism by using such materials, the recycling process itself can be highly polluting within China.

The country’s recycling industry is highly decentralized and poorly regulated. Workers in the industry rarely take safety precautions – or even have access to proper equipment and supplies – to handle waste that is often contaminated with hazardous substances. Further, recyclers often discard unrecyclable waste into landfills or bodies of water, or simply have it incinerated.

Such practices are highly polluting and create health hazards for the local population.

As China seeks to address its myriad environmental challenges, including air pollution and water contamination, it is banning the import of waste that can cause environmental issues at home.

In a notification to the World Trade Organization, China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection stated, “We found that large amounts of dirty wastes or even hazardous wastes are mixed in the solid waste that can be used as raw materials. This polluted the environment seriously.”

It continued, “To protect China’s environmental interests and people’s health, we urgently adjust the imported solid waste list, and forbid the import of solid wastes that are highly polluted.”

Consequences of the ban

The ban on imported waste will have far-reaching effects, both within China and abroad.

In the short-term, prices of recycled goods have plummeted as collectors desperately seek new buyers, while waste inventories are immobile and piling up. For example, Hong Kong’s waste paper collection points have reportedly become overloaded since the ban was announced, while cargo ships loaded with paper meant for recycling have been stuck in port with no destination.

In the long-term, manufacturers in China will face higher costs for materials as they buy from other sources. Many manufacturers may have to make up for the shortfall in plastics, for instance, by purchasing from petrochemical companies.

Meanwhile, waste collectors may have to store their waste until they can find new markets. Developed countries that are used to exporting their waste now face a more pressing need to develop technology that makes waste sorting more efficient and reduces contamination levels.

The ban is not China’s first attempt to regulate the industry. In 2011, the Ministry of Environmental Protection issued regulations on the import of foreign waste, but its implementation was questionable. Most notably, Operation Green Fence, which environmental authorities launched in 2013, sought to curb imports of low quality waste.

China has instituted the latest ban in tandem with an inspection campaign within the industry. Through the first two weeks of the campaign, from July 1 to July 14, regulators inspected 888 plastic recycling factories. Of those, 590 violated certain rules, 383 had their production suspended, and 53 were shut down.

Chinese President Xi Jinping recently announced his goals for China to become a leader in pursuing “ecological civilization”. As China continues to modernize its industrial processes and combat its vast environmental problems, more stringent regulation of polluters – and possibly additional bans on waste imports – is likely.

The complete list of products included in China’s waste import ban is as follows:

http://www.china-briefing.com/news/2017/10/24/china-ban-imports-foreign-waste.html